This document discusses the EU Data protection directive's [DPDirective] articles which are particularly interesting for federated identity management and an interfederation service. The other provisions of the directive and its implementations are naturally binding as well, but the provisions presented here have been identified as those which need coordinated functionality from the Home Organisations and Identity and Service Providers.

This document is based on the current Data protection directive [DPDirective], Article 29 Working Party's (the EU body contributing to the uniform application of the Data protection directive) opinion on consent [WP29Consent] and a legal advice given by DLA Piper to the eduGAIN project [DLAPiper]. The directive is implemented via national law in the EU member countries and, as a result, there is some variation in the legal requirements from one country to the next.

The European Union is currently reviewing its data protection related legislation.

1. Objective of the Directive (Article 1)

The objective of the directive is to protect a person’s fundamental rights while guaranteeing the free flow of personal data between member states. Thus, the directive can be seen as an enabler, not as a disabler, of federated identity management, providing the Attribute release is implemented in a way that follows the provisions of the directive.

1. In accordance with this Directive, Member States shall protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons, and in particular their right to privacy with respect to the processing of personal data.

2. Member States shall neither restrict nor prohibit the free flow of personal data between Member States for reasons connected with the protection afforded under paragraph 1.

2. Definition: Personal Data (Article 2a)

'Personal data' shall mean any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person ('data subject'); an identifiable person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identification number or to one or more factors specific to his physical, physiological, mental, economic, cultural or social identity;

In the context of federated identity management, the data subject is the end user who needs to be authenticated and whose Attributes need to be released from his/her Home Organisation to the Service Provider. In this document, the data subject is referred to as an end user or simply a user.

It is obvious that common Attributes such as end user's full name (cn), email address (mail) and unique identifier (eduPersonPrincipalName) are personal data. However, it is questionable if other Attributes such as privacy-preserving bilateral identifiers (eduPersonTargetedID/SAML2 Persistent identifier) are personal data. Following is a brief discussion of this question.

The only property the eduPersonTargetedID Attribute has is that it has the same value when the same end user visits the same service again. The interpretation of the expression relating to an identified or identifiable natural person seems to vary country by country. The directive seems to make no difference between identification and recognition, the latter meaning that the service notices the end user is the same one who has visited the service earlier, although it does not know who he is in real life.

This case is fundamentally similar to the use of an IP address; the end user is recognised by his/her IP address, but an end user's identity cannot be deduced from it. Case law is available in the Member States. One German court (Berlin Regional Court 23 S 3/07) decided that the IP address is personal data. Another German court (Munich district court 133 C 5677/08) decided that it is not. It is obvious that it is hard to get a pan-European interpretation if IP address or eduPersonTargetedID is personal data. To be in the safe side, it should be assumed that also eduPersonTargetedID is personal data.

However, in a legal advice by DLA Piper [DLAPiper] to the eduGAIN project, it is recommended that all Attributes exchanged between Home Organisations and Service Providers are assumed to qualify as personal data. Even pseudonymised identifiers (such as, eduPersonTargetedID) and role Attributes (such as, eduPersonAffiliation) alone count as personal data because the end user’s Home Organisation can always link the Attributes back to the actual end user. Only Attributes that would be completely anonymised (i.e. when even the Home Organisation can no longer trace them back to the actual end user) will fall outside the scope of the Data protection directive.

3. Definition: Processing of Personal Data (Article 2b)

'Processing of personal data' ('processing') shall mean any operation or set of operations which is performed upon personal data, whether or not by automatic means, such as collection, recording, organization, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, blocking, erasure or destruction;

Based on the definition, it is obvious that a Home Organisation processes its end users' personal data (including user accounts and Attributes) and the directive is applied to it. Registering an Identity Provider to a federation does not change the Home Organisation's status here.

Service Providers are processing personal data if they collect any information (either Attributes from an Identity Provider or directly from the end user him/herself) that is considered to be personal data. In the previous section it was recommended to assume any Attribute retrieved from a Home Organisation to qualify as personal data.

A common interpretation of the directive is that when an Identity Provider passes Attributes carrying personal data to the Service Provider, the Identity Provider disseminates an end user's personal data to the Service Provider, even though technically in the front-channel binding of the SAML 2.0 authentication request protocol, it is the end user who uses his/her web browser to carry the SAML assertion to the Service Provider. There is no known case law where this assumption is verified. If an Identity Provider is not passing personal data to the Service Provider, but it is the end user him/herself that passes the SAML assertion to the Service Provider, then most requirements presented in this document are no longer relevant. An end user can use his/her personal data as they want.

Some federations have a distributed architecture, each Home Organisation operating an Identity Provider of their own. Typically, the role of the federation operator is to maintain a trusted list of all registered Identity and Service Providers (known as federation metadata). In its legal advice [DLAPiper] to eduGAIN project, DLA Piper took the view that the metadata made available by the federtions and interfederations does not generally qualify as personal data (with the exception of the contact details of the IT administrators included to the metadata). In such a federation, the federation operator is not processing personal data.

On the other hand, if the federation operator is also operating Identity Provider(s) on behalf of the Home Organisations, they are processing personal data. Therefore, they may have a data processor status, which is discussed next.

4. Definition: Data Controller and Processor (Article 2d,e)

'Controller' shall mean the natural or legal person, public authority, agency or any other body which alone or jointly with others determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data; where the purposes and means of processing are determined by national or Community laws or regulations, the controller or the specific criteria for his nomination may be designated by national or Community law;

'Processor' shall mean a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or any other body which processes personal data on behalf of the controller;

Originally the distinction between the controller and processor was straightforward: controllers had independence in choosing how personal data were used; processors did not have any independence as they only did what they were asked to do by the Controller. However, in practice, various types of joint and sub-contracted activity are organized in ways that do not neatly fit that model.

4.1. Home organisation's position

A research and higher education institution, which has registered an Identity Provider to an (inter)federation, is typically processing affiliated end users' personal data in order to support research and education in the institution. In other words, the Home Organisation is a data controller and has determined that the purpose of processing is to support institutions primary functions which are, in general, research and education.

If the Home Organisation has outsourced the operations of the Identity Provider (for instance, to the operator of the federation), then the operator of the Identity Provider may qualify as a data processor with regards to the Home Organisation.

4.2. Service Provider's position

The Service Provider's position as a data controller or processor depends on the Home Organisations role with regards to the service. When the Service Provider is a subcontractor of the Home Organisation and only uses personal data according to the Home Organisation's instructions, the Service Provider may be a data processor processing personal data on behalf of the Home Organisation. An example of this is if the Service Provider provides licensed content, such as library content or Software as a Service (SaaS), to the Home Organisation.

Article 17 of the directive makes it explicit that the data processor must have a written contract with the Home Organisation.

3. The carrying out of processing by way of a processor must be governed by a contract or legal act binding the processor to the controller...

4. For the purposes of keeping proof, the parts of the contract or the legal act relating to data protection and the requirements relating to the measures referred to in paragraph 1 shall be in writing or in another equivalent form.

In an (inter)federation, bilateral agreements between Home Organisations and Service Providers are not expected, in general. It is also possible that a Service Provider is processing personal data on behalf of some Home Organisation(s) with whom it has a data processing contract, but is also willing to grant access to end users from other Home Organisations. In this case, the Service Provider may be a data processor for some Home Organisations and a data controller for end users in other Home Organisations.

In complex environments the qualification of a party either as a data controller or processor may be difficult. Even if a Service Provider has a contract on the service with a Home Organisation, the Service Provider may have enough freedom to qualify as a data controller. DLA Piper [DLAPiper] took the view that usually the Service Providers would qualify as data controllers.

DLA Piper also proposes that when no party decides on all aspects of the data processing and both the Home Organisations and the Service Providers have their own data processing purposes, they will qualify as "joint data controllers" (see the definition of a controller above). Joint data controllers are jointly responsible for fulfilling the obligations of a data controller. Each party can be held responsible for the actions and omissions of the other parties. In case of a data breach, for example, joint liability could arise, unless it would be very clear that the responsibility lies with just one specific party (e.g., the Service Provider).

The data protection directive is applied both to data controllers and processors, but the controller is held legally responsible also for the actions and omissions of the data processor. For instance, the controller is responsible for ensuring the security and informing the end user about the data processing. In an interfederation spanning multiple jurisdictions, it is also necessary to note that the jurisdiction follows the data controller.

4.3. Federation's position

In Section 3 it was assumed that the (inter)federation does not in general process personal data. However, in its legal advice to the eduGAIN project, DLA Piper [DLAPiper] took the view that the concept of “joint data controller” (see the previous section) may apply also to the federations and interfederations. This is possible because the federations and interfederations actually define the policy and the technical characteristics of the data exchange, regulate the rights, obligations and liability of the Home Organisations and Service Providers. Such tasks lean towards a qualification as data controller, because they can qualify as “essential means”.

5. Security of Processing (Article 17)

1. Member States shall provide that the controller must implement appropriate technical and organizational measures to protect personal data against accidental or unlawful destruction or accidental loss, alteration, unauthorized disclosure or access, in particular where the processing involves the transmission of data over a network, and against all other unlawful forms of processing.

Having regard to the state of the art and the cost of their implementation, such measures shall ensure a level of security appropriate to the risks represented by the processing and the nature of the data to be protected.

This section makes it an obligation of a controller to take necessary measures to protect personal data, in particular when it is transmitted over a network, which is the case in federated identity management. If both the Identity and Service Provider are classified as data controllers, then both parties are required to take these "necessary measures".

On the other hand, the article lets the controllers balance the obligation with the implementation costs, risks and the nature of the data. It can be argued that personal data released via an (inter)federation does not represent significant risks. Especially, there seems to be no need to release Attributes which Article 8 defines as sensitive:

Article 8

1. Member States shall prohibit the processing of personal data revealing racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade-union membership, and the processing of data concerning health or sex life.

...

6. Purpose of Processing (Article 6.1b)

Personal data must be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a way incompatible with those purposes.

As noted in section 5, the institution as the controller of affiliated end user's data has defined the purpose of processing personal data. In a research and education institution, the purpose typically follows from the institution’s charter and is, in general, to support research and education.

Following the directive, the institution must obey this purpose including when, acting as a Home Organisation, it releases Attributes to a Service Provider. The purpose of processing personal data in the Service Provider may not conflict with the purpose of processing in the Home Organisation. For example, a Home Organisation is not conflicting with the directive when releasing student's data to a Learning Management System in another university, but releasing students' personal data to a gambling service is hardly "supporting research and education".

7. Relevance of the Personal Data Processed (Article 6.1 c)

Personal data must be adequate, relevant and not excessive in relation to the purposes for which they are collected and/or further processed.

A Service Provider may process only those Attributes that are relevant for the service, whether gathered from the end user him/herself, from a Home Organisation or from some other source. In federated identity management, relevance of personal data translates to the principle of "minimal disclosure"; an Identity Provider may release only relevant Attributes to a Service Provider.

In an identity federation, the concept of an Attribute Release Policy (ARP, having its origins in the Shibboleth software) is commonly used for expressing which Attributes an Identity Provider releases to which Service Providers. For scalability reasons, in a large (inter)federation, some centralised mechanism to mediate Service Providers' Attribute Requirements to all Home Organisations and their Identity Providers is desirable. It can be assumed that the Service Provider is in a key role here; the Service Provider is the expert of the service.

8. Informing the Data Subject (Article 11)

Information where the data have not been obtained from the data subject

1. Where the data have not been obtained from the data subject, Member States shall provide that the controller or his representative must at the time of undertaking the recording of personal data or if a disclosure to a third party is envisaged, no later than the time when the data are first disclosed provide the data subject with at least the following information, except where he already has it:

a) the identity of the controller and of his representative, if any;

b) the purposes of the processing;

c) any further information such as

the categories of data concerned

the recipients or categories of recipients

the existence of the right of access to and the right to rectify the data concerning him/her

in so far as such further information is necessary, having regard to the specific circumstances in which the data are processed, to guarantee fair processing in respect of the data subject.

The data controller needs to inform the end user on processing his/her personal data. For a Home Organisation, informing the end user is obvious and can be done when a new end user gets his/her account at the institution. At that time, the Home Organisation has the first opportunity to inform that the user's Attributes may also need to be released to a Service Provider when he/she wants to access it. However, the article requires that, additionally, the end user needs to be informed about the specific Attribute release every time his/her Attributes are to be released to a new Service Provider.

The Service Provider's obligation to inform the end user depends on if it is a data processor or a controller. As a data controller, a Service Provider is responsible for communicating with the end user the issues above; which Attributes it will be using, and what it will be doing with them. As a data processor a Service Provider can refer to the Home Organisation.

The Article 29 Working Party (the EU body contributing to the uniform application of the Data protection directive) took the view that the information must be given directly to individuals - it is not enough for information to be "available" somewhere [WP29Consent, p.20]. In the Internet, a standard practice to inform the end user on processing his/her personal data in services is to provide him/her a Privacy Policy web page in the service.

In the Web Single Sign-On scenario of SAML 2.0, a convenient place to inform the end user is at the Home Organization before the Attribute release takes place for the first time. Several federations supporting the European higher education and research communities have already developed tools implementing this approach (e.g. the uApprove module implemented for Shibboleth, the consent module implemented for SimpleSAMLphp). This allows the user's decision to directly affect the transfer of Attributes to the Service Provider; if the Service Provider were communicating with the user it might have already received all the Attributes and values.

9. Criteria for Making Data Processing Legitimate (Article 7).

Personal data may be processed only if:

(a) the data subject has unambiguously given his consent; or

(b) processing is necessary for the performance of a contract to which the data subject is party or in order to take steps at the request of the data subject prior to entering into a contract; or

(c) processing is necessary for compliance with a legal obligation to which the controller is subject; or

(d) processing is necessary in order to protect the vital interests of the data subject; or

(e) processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller or in a third party to whom the data are disclosed; or

(f) processing is necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by the third party or parties to whom the data are disclosed, except where such interests are overridden by the interests for fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject which require protection under Article 1 (1).

In summary this article concludes that data processing can be based either on consent or necessity. If based on consent, it must be freely given (an end user must have an option to say no), specific (given to each Service Provider separately) and informed (an end user must understand to what he consents -- see the previous section).

(Article 2 h) 'The data subject's consent' shall mean any freely given specific and informed indication of his wishes by which the data subject signifies his agreement to personal data relating to him/her being processed.

Historically, there seem to be two interpretations of this article. In some countries, consent has been the primary way of making data processing legitimate. In other countries, consent should be used only as a last resort, and the desirable way is to base processing of personal data on some other legal grounds whenever possible. To harmonise the use of consent as a legal basis for processing, the Article 29 Working Party has used an employment relationship as an example where consent may not be valid legal grounds. An employee is in a situation of dependence on the employer and might fear that he could be treated differently if he does not consent [WP29Consent, p.13].

9.1. Necessity legal grounds

Alternatively, data processing may be based on necessity, for example:

- Providing education to a student (c, e, f)

- A teacher, researcher or other employee to do the jobs his/her employer has assigned to him/her (b, f)

However, deciding if a service is necessary or not is cumbersome. If a student is taking a course which is mandatory in his/her curriculum, release of personal data to the course's learning management system is probably necessary. But what if the course is optional? If a researcher is using licensed contents related to his/her subject of research, release of personal data is probably necessary, but what if the researcher is browsing contents outside his/her subject of research? As a result, the decision of whether Attribute release is based on consent or necessity becomes a complex function of (Service Provider, end user, time).

In a legal advice provided to the eduGAIN project, DLA Piper [DLAPiper] recommends that, to avoid the difficult deduction if consent is valid legal basis, the Attribute release could rely always on the ‘legitimate interests’ legal grounds defined in Article 7.f. Unfortunately, there is some uncertainty in this, because it expects balancing the end user’s fundamental rights and freedoms and the data controller’s interests. Anyway, DLA Piper sees reliance on this legal grounds justified, taking into account the general privacy-protecting setup of the data flows in a federation, the low level of risk posed by the personal data being exchanged and the innocuous (mainly scientific) type of services accessed by the end users. This would also relieve the data controller from the practical issues relating to withdrawal of consent, and difficulties in managing the consent for children under the legal age.

9.2. Releasing optional extra Attributes on user consent

Additionally, Article 29 Working Party's opinion on consent [WP29Consent, p.8] implies that several legal grounds for processing can be used simultaneously. For instance, processing may be necessary under the balanced legitimate interests (Article 7.f), but additional information may be collected on the user's consent (Article 7.a). Applied to an identity federation, the Attributes necessary for identification and authorisation of the end user and personalising the service for him are released under the legitimate interests legal grounds (Article 7.f), but the end user may also consent to the release of extra Attributes (Article 7.a), in order to enjoy some higher service level.

For instance, for a wiki service, release of eduPersonTargetedID (identification) and eduPersonAffiliation (authorisation) could be necessary for the legitimate interests of the data controller. If the users constitute a community also in the real world, it can be argued that release of the full name (personalisation) is also necessary for transfering the existing user community to the wiki. On the other hand, release of the email address to the wiki could take place on user consent, because it would let the user subscribe to an optional additional service of receiving email notifications from the wiki.

Alternatively, the Service Provider may gather additional information directly from the user him/herself, e.g. ask him/her to type in his/her email address and other profile data. The user's Home Organisation and Identity Provider is not involved in this. This approach may be simpler in some cases.

A property of consent is that it can be withdrawn any time. According to Article 29 Working Party, in principle, consent can be considered to be deficient if no effective withdrawal is permitted [WP29Consent, p.13]. If withdrawal of consent makes the service break for the user, consent has probably been the wrong legal basis for processing.

According to Article 29 Working Party, consent has to be given before the processing starts [WP29Consent, p.9]. Using consent as the legal basis requires some additional work from the Identity Provider which needs to install a consent module (such as, uApprove for the Shibboleth software). If hybrid scheme is used, the module should be able to ask user consent for only those Attributes whose release is based on consent, and provide the user an opportunity to consent for each Attribute individually. The release of the other Attributes would be without user consent, based on the legitimate interests legal grounds. However, once installed, the consent module can be used also for informing the end user (see section 8).

Finally, it is worth noting that consent does not override the other obligations imposed by the directive, including the purpose of processing, relevance of personal data processed and informing the data subject. It is wrong to assume that anything can be done with an end user's personal data if he consents to it.

10. Release of Personal Data to 3rd Countries

Personal data may be released to other EU and EEA (Norway, Iceland, Lichenstein) countries as it is released within an EU/EEA country. The directive recognises that also some non-EU/EEA countries (dubbed as 3rd countries in the directive) may have adequate level of data protection. Personal data can be released to those countries just as it is released to any EU/EEA country. In federated identity management, this principle is applied to non-EU/EEA Service Providers.

The European Commission publishes a list of countries with adequate level of protection. For instance, in Switzerland and Argentina, data protection laws ensure adequate level of protection. Canada has sector-specific data protection legislation, and the protection is adequate if the Canadian data controller is subject to the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act.

The Service Provider's jurisdiction follows the data controller. If the Service Provider is a data controller, the Service Provider's local laws on data protection are applied to the Service Provider. If the Service Provider is a data processor (i.e. processes personal data on behalf of the Home Organisation), the Home Organisation's laws are applied.

To release personal data to countries that do not guarantee adequate data protection, the level of protection must be ensured in an agreement with the data recipient. The European Commission has published related model contracts for the transfer of personal data to third countries. In federated identity management, the Attribute release takes place between the Home Organisation and the Service Provider, who should sign an agreement which commits the Service Provider to an adequate level of protection.

In a (inter)federation, direct contracts between Home Organisations and Service Providers are not expected in general, which suggests that this Code of Conduct alone cannot be used by Service Providers who are not bound to an adequate level of protection by the local law. This does not exclude non-Europan Service Providers or even federations to receive Attributes from Home Organisations in EU/EEA, but their data protection issues must be solved using some other mechanism.

11. Receiving Personal Data from 3rd Countries

The directive is applied to processing personal data in EU/EEA, regardless of the Service Provider processing personal data on behalf of a data controller in a 3rd country or not. However, if the Service Provider is a data processor and the data controller is in a 3rd country, the directive expects the data processor to have a representative in EU/EEA to ensure the directive can be enforced:

(Article 4) 1. Each Member State shall apply the national provisions it adopts pursuant to this Directive to the processing of personal data where:

...

(c) the controller is not established on Community territory and, for purposes of processing personal data makes use of equipment, automated or otherwise, situated on the territory of the said Member State, unless such equipment is used only for purposes of transit through the territory of the Community.

2. In the circumstances referred to in paragraph 1(c), the controller must designate a representative established in the territory of that Member State, without prejudice to legal actions which could be initiated against the controller him/herself.

If the Home Organisation outside EU/EEA has a data controller/processor relationship with any of the Service Providers in EU/EEA, it needs a representative in EU/EEA. On the other hand, if the Service Provider in EU/EEA is a data processor for a non-EU Home Organisation, it needs to have a written agreement with the non-EU Home Organisation anyway (see section 4.), and the EU/EEA representative is covered there. In the (inter)federation agreement, the requirement for a non-EU/EEA Home Organisation having a representative in EU/EEA can be omitted. The Home Organisation does not need to reside in a country which guarantees adequate level of data protection.

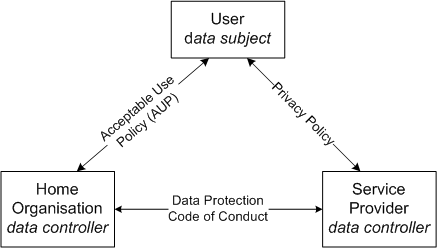

12. The triangle of data protection relationships

The following triangle may ease a reader to understand the data protection related relationships between the parties and the documents governing them

- The user's and his/her Home Organization's relationship is covered by the Home Organisation’s AUP (acceptable use policy) agreement with the user.

- Typically, an emploee, student and other end user accepts the Home Organisation's AUP when he/she receives his/her user account.

- The Home Organisation has an opportunity to inform the user on his/her personal data processing when he/she accepts the AUP

- The user's and Service Provider's relationship is covered by the Service Provider’s privacy policy

- This Data protection Code of Conduct is proposed to cover the relationship between the Home organization and Service Provider.

- Additionally, the Home Organisation and Service Provider may have other agreements, such as a data processor/controller agreement. Those agreements are proposed to take precedence over the Code of Conduct.

13. EU laws factored to concrete requirements

In this section, the provisions presented above are factored into concrete design requirements for an (inter)federation. Where appropriate, this section also proposes a scalable division of responsibilities between the Home Organisation and Service Provider.

- General responsibilities of the Home Organisation and Service Provider

- The Home Organisation and Service Provider MUST take necessary measures to protect personal data, in particular when it is transmitted over a network.

- A Home Organisation cannot release Attributes to a Service Provider without "implement(ing) appropriate ... organizational measures" to ensure that the Attribute release doesn't result in unlawful processing.

- Minimal disclosure

- All Attributes exchanged between Home Organisations and Service Providers are assumed to qualify as personal data (including role Attributes, such as eduPersonAffiliation).

- A Service Provider MUST publish the list of Attributes that are adequate, relevant and not excessive to the Service.

- A Home Organisation MUST have confidence that all of the Attributes requested by the Service Provider are relevant to the service.

- A Home Organisation MUST release only the relevant Attributes to the Service Provider

- A Service Provider MUST lower the risk for all parties by

- deciding to request lower risk kinds of data (for example, eduPersonTargetedID instead of eduPersonPrincipalName).

- for multi-valued Attributes, indicating the subset of values it needs (for instance, eduPersonAffiliation="student", c.f. saml:AttributeValue).

- INFORMing the end user

- The end user MUST be presented with information at least about:

- the identity and contacts of the Service Provider

- the Service Provider's purpose of processing personal data

- the categories of data to be released

- the existence of the right of access to and the right to rectify the data concerning him/her

- A Service Provider MUST publish a publicly readable Privacy Policy page which covers the information above.

- The Privacy Policy page's link

- MUST be provided to the user in the service's landing page

- MUST be mediated to the Identity Provider

- To balance privacy and usability, a Home Organisation MAY apply a layered approach to fulfill the obligation to inform the end user

- 1st layer: The Identity Provider deploys an Attribute release module, which

- shows the Service Provider's name (c.f. mdui:DisplayName)

- shows a short description of the service (c.f. mdui:Description)

- shows a list of Attributes and their values that are to be released to the Service Provider (c.f. md:RequestedAttribute)

- provides a clickable link to the Service Provider's Privacy policy (c.f. mdui:PrivacyStatementURL)

- 2nd layer: the Service Provider's Privacy policy complements the 1st layer by additional information

- the identity of the controller and of his/her representative

- the existence of the right of access to and the right to rectify the data concerning him/her

- the data retention period

- any other information relevant to the end user

- The end user MUST be presented with information at least about:

- Legal grounds: necessary for the legitimate interests or consent

- A Service Provider MUST specify the legal grounds for the processing of each Attribute that it requests (c.f. @isrequired="true").

- Two of the legal grounds for Attribute release are relevant to Higher Education/Research situations: "legitimate interests pursued by the data controller" and "user's consent" (for release of extra Attributes which are not necessary but offer the user an optional higher service level).

- The user MUST be INFORMed when Attributes are being released due to the legitimate interests legal grounds (see above).

- The user MUST be INFORMed and give his/her CONSENT when Attributes are released due to the consent legal grounds.

- Releasing optional Attributes based on user consent

- The user MUST give his/her consent to the Home Organisation before optional extra Attributes are released.

- The user's consent MUST be freely given (an end user must have an option to say no), specific (given to each Service Provider separately) and informed (an end user must understand to what he consents).

- If several Attributes are released based on consent, the user MUST be able to give his/her consent individually to each Attribute. Consent to "all or nothing" is not sufficient.

- A user can be asked to consent to the release of a named "group" of similar Attributes (for instance, a user could be asked to consent to release "name", and this single consent would allow the release of commonName, surName, givenName and displayName).

- If an Attribute has multiple values being released, consenting to release of the Attribute is sufficient to release all of the values.

- There MUST be a way for the user to withdraw his/her consent for release to a specific Service Provider after having previously granted their consent (even if they have previously said they'll never want withdraw it). If they access that Service Provider in the future, they would be re-prompted. However, withdrawing consent does not require a Service Provider to discard previously received Attributes. The user him/herself can use the Service Provider's Privacy Policy to contact the Service Provider in that matter.

- The Identity Provider MAY remember the user's consent decision and not prompt him/her again when he/she accesses the same Service Provider for the next time. For usability reasons, this may be desirable.

- For audit trail, the Home Organisation MUST ensure that reliable log entries are stored on users' decisions to consent to Attribute release.

- Service Provider Processing Received Attributes

- Before accepting any Attributes whose release is indicated to require user's consent, the Service Provider MUST be confident that the Home Organisation has properly acquired user consent for the Attribute release.

- Attributes MUST NOT be released to a Service Provider located outside of the EU/EEA or in country which does not quarantee adequate data protection, unless the Service Provider protects them as the EU law expects and has made assertions that their practices are in compliance with EU regulations.

References

[DPdirective] Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. Available in: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31995L0046:en:NOT

[DLAPiper] DLA Piper. Data Protection analysis eduGAIN project. Memorandum. 29 June 2011 (pdf).

[WP29Consent] Article 29 Working Party. Opinion on Consent. Available in https://ec.europa.eu/justice/article-29/documentation/opinion-recommendation/files/2011/wp187_en.pdf